In 1986 I was in my second year at art school when the British photographer, Jo Spence, published the book “Putting myself in the picture”. Spence’s critical documentary practice was a feminist critique of representation and it was an inspiration. In one of the final images in this book she captions one of her photographs with “Someday my prints will come”. For me, maybe as for Spence, art is the prince on the white charger.

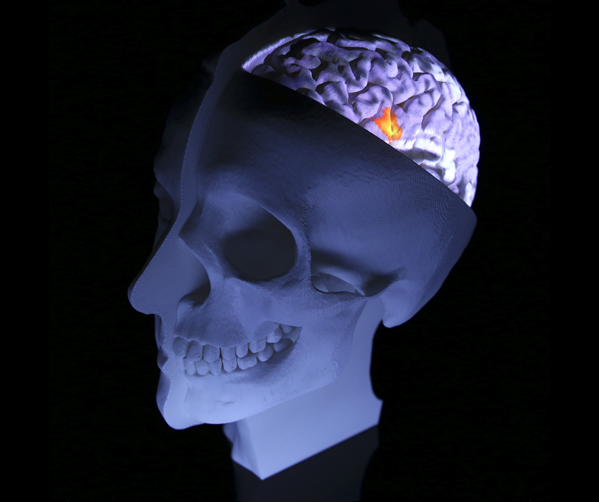

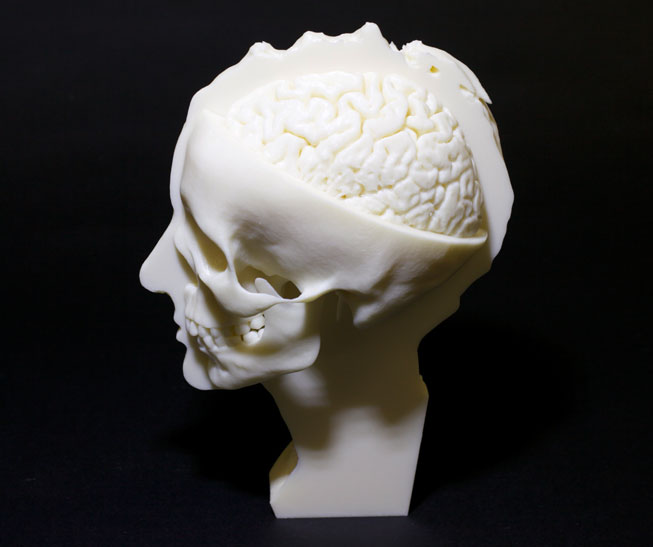

I wait for delivery of 3D prints, much as she waited for her silver-based photographs to arrive. When I saw this timelapse of one of the sections my Neuro Memento Mori piece being printed, I immediately thought of Spence, her witty “Someday my prints will come” and her series ‘The Final Project’, made with her long term collaborator, Terry Dennett.

Image copyright Jo Spence and Terry Dennett. Final Project (death rituals and return to nature series), 1991-92

Image copyright Jo Spence and Terry Dennett. Final Project (death rituals and return to nature series), 1991-92

In the last two years of her life, 1991-1992, she made these memento mori works as she thought about her death. One photograph in particular strikes me. The face is a mask with empty eyes, a double exposure that seems to catch a moment of slippage, where the face pitches to one side, revealing the skull beneath. The skull. Always there, the hidden scaffold for our lively expression that remains after our eyes empty and our flesh rots.

Next week Art Basel Hong Kong begins. A good time to “Remember You Must Die” to think about the transience of life and art, its futility. To remember, and celebrate, art’s pointlessness and the inevitable but useless joy of anticipation.

Someday my dark prince/prints of death will come.