Make critical arguments that account for why a well known key text or theory is not pertinent to your research. Do not just omit a key area and hope your overall argument makes it obvious why you are not discussing X or Y seminal idea or text. By making a critical argument and referring to the text you let the reader know, by ‘showing’ not ‘telling’, that you understand that text, that you know it exists. If done well, this means the reader does not need to question further any apparent ‘omission’ of key thinkers later in the thesis.

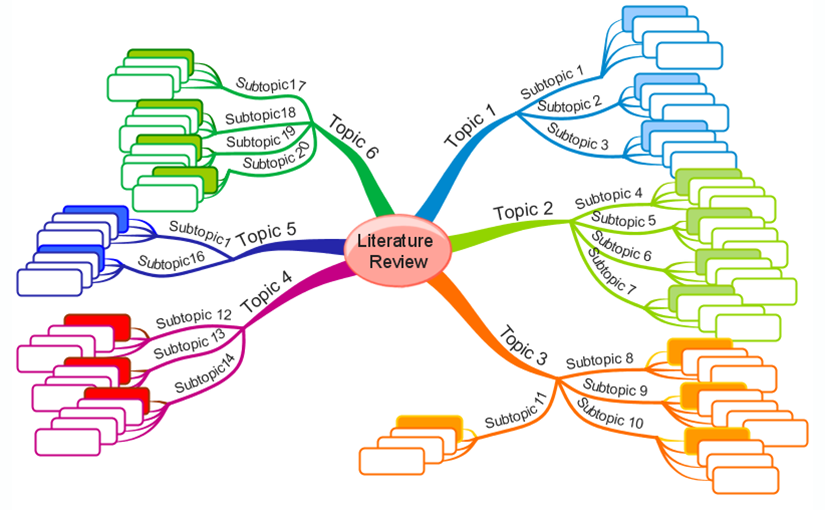

This is part of good research writing practice for your PhD, what I often refer to as “relaxing the reader, the examiner”. In this case, by concisely explaining why an apparently key text is not central to your Literature Review, you stop the examiner making a note and wondering whether you have worrying gap in your knowledge. Do this in one or two sentences. These should acknowledge and summarise the role of that text or theory, very briefly. Other knowledge domains may be omitted because you “can’t cover everything” and they are not central enough to the domains you are covering. In such cases, again, reassure the reader that you know your stuff, that you DO know about that domain. Explain why it is not coming into your thesis, which again adds to your credibility as a scholar. End that couple of sentences with a statement such as, “it is therefore beyond the scope of this research to discuss X further.” This applies to all disciplines and the example below, while conversational in tone. illustrates why eliminating areas is good for you as a researcher.

“At CERN, there was a video where a particle physicist was asked “What if you don’t find the Higgs Boson? What if you’re wrong about this?” and he thought that would be brilliant, because then they’d know a whole area they could block out and go OK, not this, but how about this?”

James Bridle, http://booktwo.org/notebook/sxaesthetic/

As an examiner, if I have to read through the thesis and ‘guess’ why X or Y key thinker has been omitted I question the depth and breadth of the work being presented. If I am told clearly early on, with a convincing argument, I have one less question for you at the Oral Examination and this contributes to me believing that you know your stuff.