The post title is a quote from William Mountfort’s play, “Zelmane”, 1705

Critical cartographers, like Amy D. Propen suggests that we engage with a map “as something that both socially constructed and as purporting to represent a “correct” model of the physical world” by understanding cartographic practice as embodied knowledge. This seems especially relevant when engaging in neuro cartography, or mapping the brain, as this practice – the production of neuroimages – depends on living, embodied, brains.

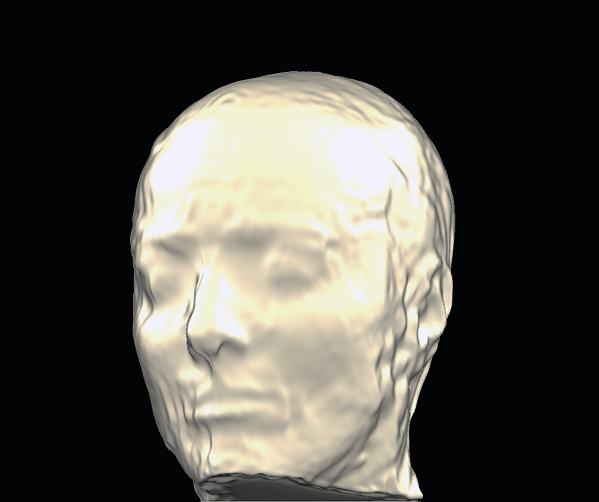

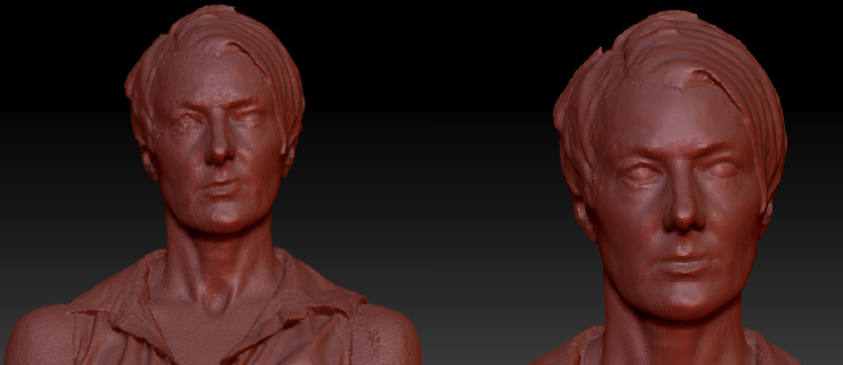

To get the clearest neuroimages my body and brain need to remain very still for the 5-10 minutes that a functional MRI scan takes to complete. This need for stillness makes me self-conscious and that accentuates my sense of being embodied. As I try to control my body and stay still, I become hyper aware of what are usually unconscious and small bodily movements associated with breathing or swallowing. To move while being scanned adds noise to the data, blurring the image, and therefore the most scientifically useful MRI image emerges through intra-actions that partially erase the trace of my body. ‘Playing dead’ is an essential part of imaging my living brain.

For more see Amy Propen, “Cartographic Representation and the Construction of Lived Worlds: Understanding Cartographic Practice as Embodied Knowledge.” Rethinking Maps. Ed. Martin Dodge, Rob Kitchin, and Chris Perkins. New York: Routledge, 2009. 113-130.

See also, Joseph P. Hornak’s online book, “The Basics of MRI” online.